Never Excuse as Stupidity

On Criminal Negligence In Governance

On the 14th of March 1757 Royal Navy admiral John Byng was executed by firing Squad.

The Execution of an admiral even in his day was nigh unheard of, even amongst the absolute monarchies of continental Europe such things were almost never done…given the importance an Admiral inevitably had to aristocratic social balance and tone of upper-class society, even deeply shamed and dishonored Admirals usually escaped such formal and final denunciation… Pensions were reduced or stripped, commands and ranks regularly lost, lands and titles even on occasion, and social death was a major threat when this would affect not just the outcome of one’s own life, but the marriage and social prospects of children and cousins throughout the family…

But execution? Published as a matter of official record to the masses? In an era when saving face and putting on a strong show of unity could spell the difference between nations rising and falling….

What the hell had Byng done? Not to be executed even at the hand of a capricious absolutist king… but that of a constitutional monarchy run by a parliament such as Britain?

Had he been caught in treason? Had he proven the gravest of cowards in the face of the enemy? Had he embezzled funds? Had he personally despoiled the chastity of the first princess?

None of this.

Byng had “Failed to do his utmost”.

.

Minorca is a small Island near Spain in the Mediterranean that had been a British possession since its capture in the War of Spanish Succession (1708)… but by the 7 Years War (1756-1763) British presence in the Mediterranean had shrunken perilously small.

So in 1756, Byng was to sail and relieve the Island. Byng’s fleet left Britain understrength, holding only 6 of 10 ships. Those ships were undermanned, nor was he given time or money to outfit them. Byng protested, yet nothing was to be done and he sailed short ~800 men. Along the way, he found intransigence and flat refusal of orders and commanders unwilling to hand over entire units he was to command at British ports.

None the less he arrived with his now 16 ships at Minorca and made battle with the French.

The battle of Minorca was not a great historic affair.

There are dramatic battles in history: When small forces turn back vastly larger foes, or one fortunate turn breaks an army, or men grind themselves against each other harrowingly for hours or days… Battles where the fates of nations turn on the wills, wits, and daring of men who somehow strike figures larger even than the chaos, or are consumed by their horrific lacking beneath the world’s cruel indifference…

Minorca was none of that.

The Attacking English Initially gained the weather Gauge (the wind at their backs) and control of the battle, and were prepared to move in a line and one after another broadside the French as they struggled to maintain formation… but then due to a miscommunication they fell out of formation and it turned into a simple rolling fight between the two. About even casualties were suffered by both sides, at which point the French managed to break contact and sail away.

And here is the fateful moment. Byng assessing his strength, the damage to his ships, and the state of his crew, decided not to pursue, and instead gave the order to return to Gibraltar where they would perform repairs and, it was thought, subsequently launch another attack on the besieging French fleet. They never would.

Shortly after Letters arrived relieving Byng of Command and ordering his return to Britain.

He was to be court-martialed, and after the court martial, he was executed.

Perhaps the mundaneest of battles, inconclusive, insubstantial, and uninteresting had become the seed of one of the most extraordinary events in human history.

.

Now many have argued Byng’s execution was a politically motivated affair, indeed it is hard to deny it was.

Byng’s report of the events at Minorca only made it to Britain weeks after the French report, a report which given they were the enemy, painted the French in a positive light holding off the British relief, whilst Byng and the British faltered, hesitated, and were shown of by French daring and manliness (leave it to the French to brag about a battle they fled).

This left the British public apoplectic. having come off a series of defeats, Byng’s failure to press the attack moved the public to, literally, burn him in effigy (they genuinely made effigies of him and burned them in the street).

Many commentators have argued then and now that Byng was scapegoated for the frustrations of the entire empire… indeed by the time of his sentence, most of the British Elite had publicly come around to sympathy for Byng… The Admiralty and Navy pleaded for clemency, Parliament and Prime Minister William Pitt (The Elder) begged George II to exercise his royal pardon to Commute Byng’s sentence, indeed the public themselves had started to have doubts: Were they letting the Admiralty in their offices escape by throwing a brave officer, one who’d actually faced down the French, to the wolves?

The Pardon never came.

Countless denounced the sentence as a miscarriage of justice, Admiral Forbes even refused to sign the death warrant, claiming he believed it to be illegal, instead writing a document explaining his refusal.

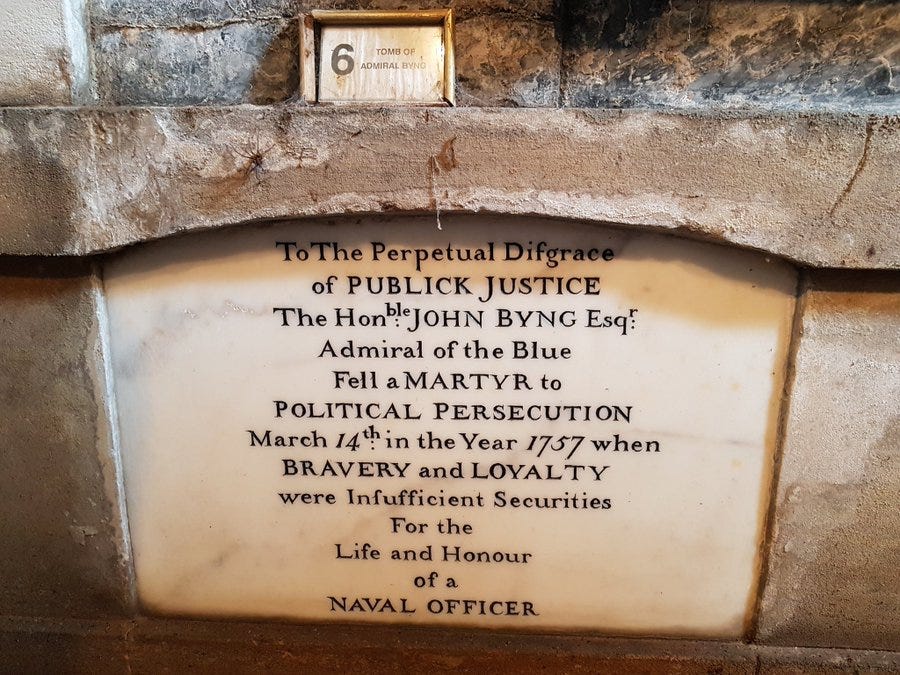

Byng’s epitaph denounced his fate, calling Byng “a Martyr to political persecution”

Byng’s family continued in its aristocratic manner with many subsequent Byngs serving with distinction in various parts of the British empire hundreds of years later.

But perhaps his most famous legacy was a quip from Voltaire in Candide: "In this country, it is good to kill an admiral from time to time to encourage the others"

Pour Encourager les Autres finding the start of its long and bloody history here.

.

Put otherwise it was the single greatest moment in institutional excellence and culture formation in human history.

Pour Encourager les Autres

The Royal Navy was perhaps the single most successful institution in human history.

That the extraordinarily small population of Britain was able to dominate a Quarter of the world’s land and population and via such a remarkably small number of people actually within the navy, a number which must be reduced vastly further when one accounts that the majority of its sailors were prisoners or impressed men for most of its history, who given half the chance would have gladly disserted or mutinied and done anything else, owes itself to the truly extraordinary skill, character, and ruthlessness of its officers.

These few thousand commissioned gentlemen ventured, often with little more information than they could gleam from a spyglass, out into the wide blue world… where the countless millions before them as well as many of the hundreds at the backs of the 3-20 officers aboard a ship, all wanted them dead…

And they ruled for nearly 200 years.